- Part 1 – The Idea – A Knight in Rome

- Part 2 – Revisions with Ralph Bruhn

- Part 3 – The Theme and Three Central Ideas

- Part 4 – The Illustrations

Part 1 – The Idea – A Knight in Rome

The basic idea of Djinn was born in late autumn of 2017 after a game of Stefan Feld’s Trajan. After playing, I kept thinking about how well the interesting core mechanism was incorporated into the game, even without it having a direct correlation to the theme or actions of the players. This inspired a new game idea based on three central ideas. But first, let’s talk about the question of theme.

Theme

Because title and theme are often chosen by the publisher, I focused instead on building the game mechanics. I wanted a generic theme for development and testing because, in my experience, it is easier to create games when the theme is familiar. Therefore, I chose the classic setting of ancient Rome and just gave it the working title Rome.

1. The Core Mechanism

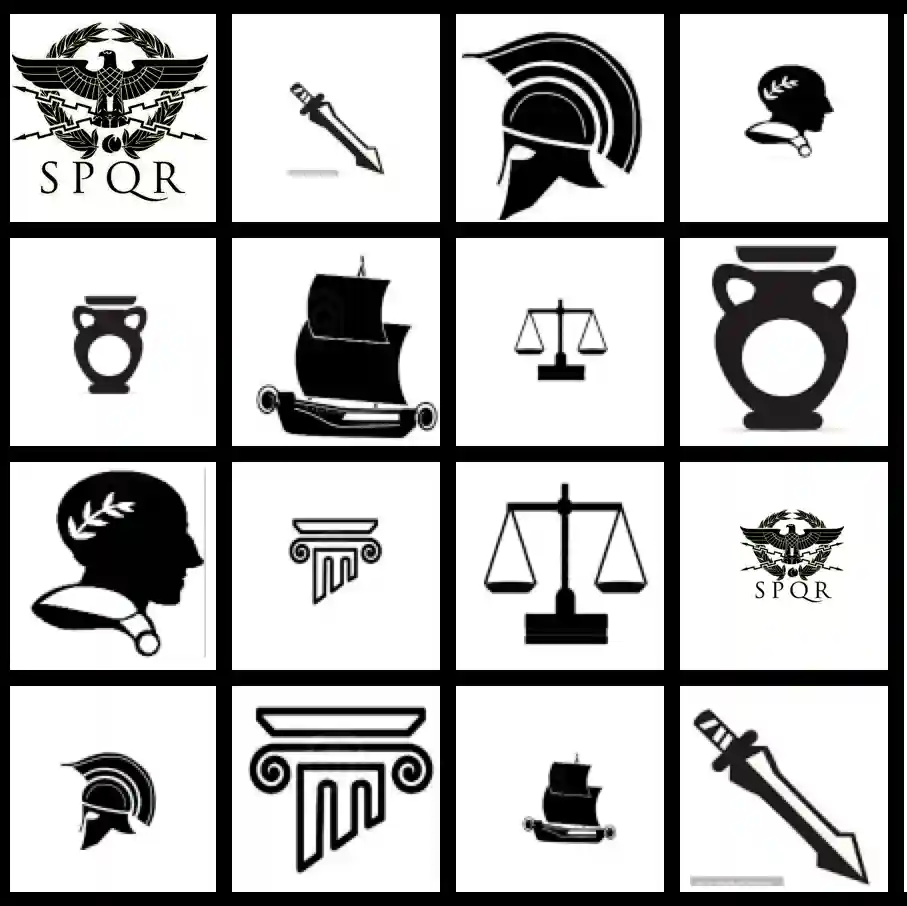

I gave some thought to which abstract mechanism I personally would love to see in a modern board game, but that had not been used much. My first idea was to set a Knight, the chess piece, on a 4×4 board. I had not seen a modern board game use this mechanism as a method of moving between squares. I especially liked the control and opportunity for planning that it offered. (Note: Uwe Rosenberg’s game Robin von Locksley from the year 2019 has a similar mechanism. I did not know this game at that time.)

Next, I assigned actions to each square in the 4×4 grid. I knew that 16 different actions would be too many, so I settled on eight separate actions, each with a strong and weak version. The alternating spatial arrangement created an interesting effect that a weak action would always be followed by a strong one. After just a little effort, there was already interesting depth of play.

This first version gave each player their own unique Player Board, with the same 16 action spaces but in a different arrangement on each board. I also added the option of improving one’s own Board by adding a marker for an additional action to any square with a minor action. Whenever the Knight moved to a modified square, the player could use both actions on their turn.

2. Few Points

Another central idea was that there should only be a few ways to gain points so that every point felt important. The points that players scored in Rome represented “golden seals,” signs of appreciation for having served and contributed to the Roman Empire.

These golden seals could be gained by fulfilling certain tasks such as the successful exploration of land or by shipping valuable goods. There were also grey seals, which were more plentiful and much easier to get than golden seals. It was also possible to exchange multiple grey seals for a golden seal, and the game was designed so that only a small number of golden seals could ever be collected. Every point felt important.

3. The Game’s End

In addition to the Player Board, there were eight separate action tableaus where players could produce and ship goods, reinforce the military and send them to explore, collect taxes, promote aristocrats, improve their position in the senate, and construct statues and buildings.

The buildings and the senate were both special actions. Constructing buildings didn’t provide any benefit during the game but was a requirement of winning—only players who built five or more buildings were allowed to tally their points at the end of the game for final scoring. It represented how the greatest citizens of Rome had to do more than follow their own private agendas…they also had to contribute to the growth and glory of Rome.

The senate had two separate functions. First, players could improve the exchange rate of grey to golden seals. Second, you could affect the length of the game and if players were fast it was possible to trigger the end of game, early. This was an important consideration for any player pursuing a long-term strategy.

Part 2 – Revisions with Ralph Bruhn

At the start of 2019, I presented the prototype to Ralph Bruhn, who owns publisher Hall Games and often works as a freelance editor for Pegasus Spiele. I produced the games Yeti and Crown of Emara with him which were published by Pegasus Spiele, both of which I was very pleased with. I especially enjoyed the constructive relationship working together with Ralph.

Neither Ralph nor I foresaw how intense and time consuming the revision of the game would be. That Rome was published four years later as Djinn was mostly because the COVID19-pandemic impeded us in the development. We needed feedback from playtesting to find and fix weaknesses of the design.

For a long time we were limited to playtesting digitally on Tabletopia. Unfortunately, when testing you not only want to confirm that the mechanisms work, but you also want to judge whether the players are having fun while playing. I have to admit the difficulty for me because playing digitally took longer and influenced the game experience negatively. When we finally were able to schedule “real” playtests again, the feedback gave us many good ideas to further improve the game. Making these final changes took us another year to complete.

It would go beyond the scope of this article to give a complete overview what we modified, converted, tested, discarded, and included in the different phases of the revision. Therefore, in the next section, I will focus on what happened to the three central ideas and the topic.

But I can say this: We removed punishing mechanics and a few luck elements. For example, we took out the rule that required buildings to stay in the game’s final scoring. These chances were not surprising to me because I knew from our previous work together that Ralph values a positive game feeling.

Part 3 – The Theme and Three Central Ideas

About the Theme

Ralph changed the theme after a few months of work and chose a magical setting. For a long time the working title was Flaschengeist (Genie) and, as you might guess from the title, the goal of the players was to catch genies.

The golden seals became genies who were worthless until they were captured in bottles. The eight separate actions were transformed to match the new theme, then were further developed. Finally, we reduced this to six actions and optimized them.

Central Idea 1 – The Core Mechanism

Special and unusual mechanisms have the downside that they can be hard to introduce to new players. For many players the original 4×4 grid was challenging to plan through all the ways the Knight piece could move, therefore it was tough to execute the actions in a sensible order.

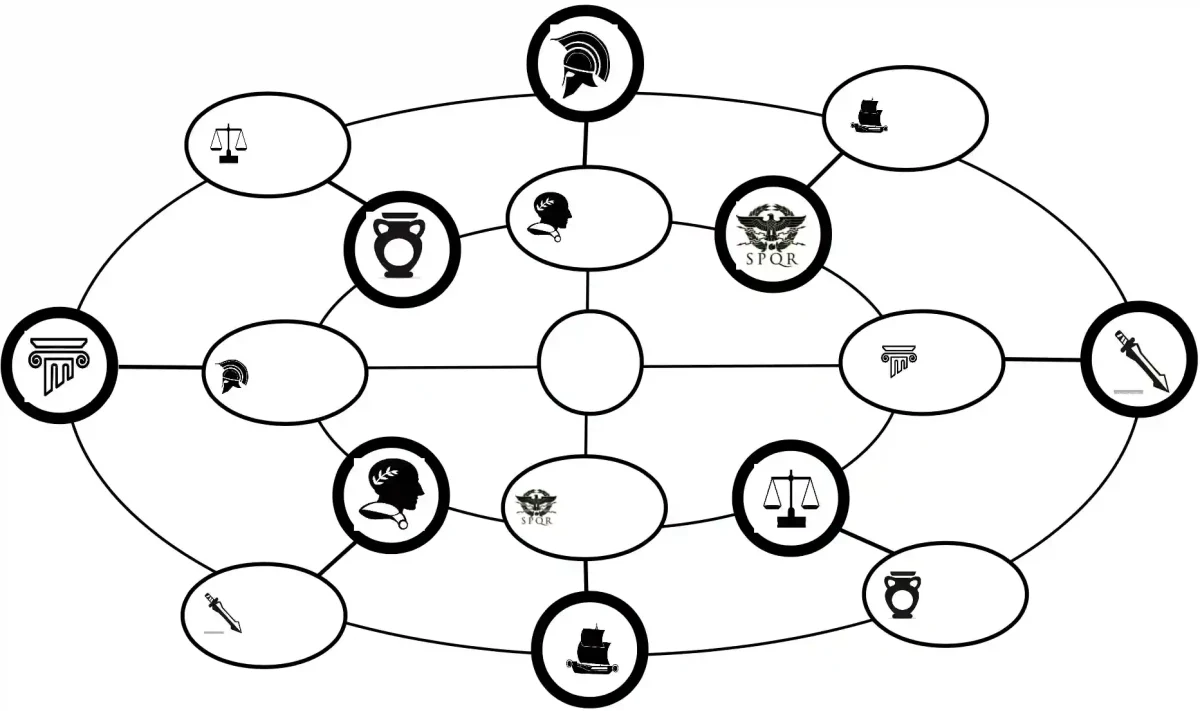

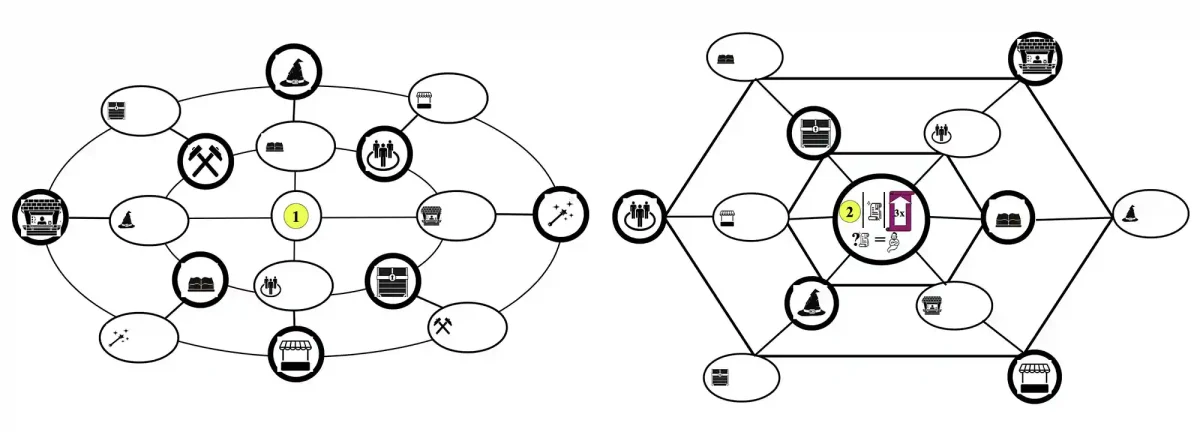

Ralph had the good idea to transform the core mechanic into a topology of paths that alternated between strong and weak actions. At each step, a player still had 2 or 3 options for their next move, but it was a much clearer layout to consider their options:

This arrangement has multiple upsides: There were no more corner spaces with fewer connections to other spaces; we could integrate an additional space in the middle; we could fix the problem of jumping between two spaces; we could reduce the system from 16 to 12 spaces. So, we replaced the Knight piece with a player figure that can never move backwards. We returned to the idea of a single common board rather than individual player boards, but still weren’t convinced and discarded it again. It seemed too confusing and big. We still needed to find space for individual upgrade markers and the Djinn pieces.

The post-pandemic-feedback brought both wishes and new ideas: paths should be shorter, actions should be better differentiated, and the game should be less of a solitaire experience and therefore less plannable. So we completely redesigned the actions and reduced them from eight to six, and also settled on a common board. This way, we increased the interaction as well as the ability to have a good overview. Even the Djinn, previously placed on action boards, would now be positioned next to the round action spaces of the central board.

The original, central starting space was improved and expanded to become a special action space:

Central Idea 2 – Few Points

The goal of the game was clear and easy: Whoever caught the most Djinn and trapped them in corked bottles would be the winner. For a long time, this was the only way to determine each player’s score; corks and empty bottles only served as tiebreakers.

Because one would likely only catch up to ten Djinn per game, every single one captured felt satisfying and rewarding. On the other hand, we discovered that we often needed the tiebreakers, and this gave the impression of randomness. The solution was to convert all three elements, i.e. Djinn, bottles, and corks, into points at the game’s end. Most of the time, capturing the largest number of Djinn would result in a victory but this new system eliminated the feeling of randomness. It also allowed us to introduce end-game scoring cards to give players more to consider.

Central Idea 3 – The Game’s End

In the early versions of the design, there were multiple ways to trigger the end of the game. This could lead to frustration because some players were left feeling that the game could end too suddenly.

We solved that issue by defining that the game ends once all six Boss Djinn have been removed from the village. The ending is now completely in the hands of the players, and there are no surprises because everyone at the table always knows how many Boss Djinn remain in the village, and who has the opportunity to reach them.

Finally, the game doesn’t end immediately the moment the last Boss Djinn is removed—everyone has 1 or 2 more actions before final scoring, so they may try to complete a plan or switch their resources for points.

Part 4 – The Illustrations

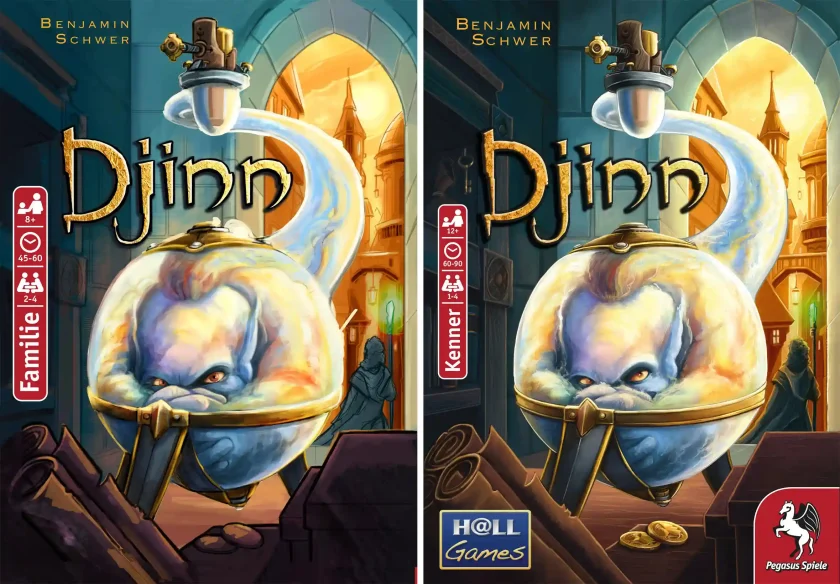

I was delighted that Dennis Lohausen agreed to illustrate the game. He already did amazing work in the graphic design of both Yeti and Crown of Emara, and I was excited knowing the visually appealing artwork we would create.

The first cover drafts already showed an interesting direction and with every new illustration we could feel the magical world of the game grow into existence.

To give insight into the illustration process, here an example of the Djinn’s design: The Djinn was not supposed to look friendly and you should not feel sympathy for him – we want to catch him after all. Neither should he look too evil, so one does not feel deterred by the cover.

Dennis created multiple versions with facial expressions where the Djinn in the bottle stared at the viewer directly. On one hand, I loved it, but on the other hand the Djinn’s look was quite hostile and scared some people. So we decided on the right draft:

Dennis did a great job with the game materials as well: the design both immerses us deeply into the setting of the game while also making the game mechanics and board state very clear for players.

He summarized what used to be the central Game Board with the six action spaces around in the prototype into one big overview board, but with recesses.

The central game board with six action boards around it of the prototype was combined together into a single, large overview board, but the strict rectangle of a typical game board has been loosened up by recesses into which cards and tiles can be docked.

In conclusion, the development of Djinn was long and work-intensive, but also very interesting, rich in variety, and an exciting journey.I’d like to thank everyone that was involved in different ways in this game and helped to enrich it.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed these little insights into the story of this game’s development, and I wish everyone has a wonderful time playing Djinn.

– Benjamin Schwer